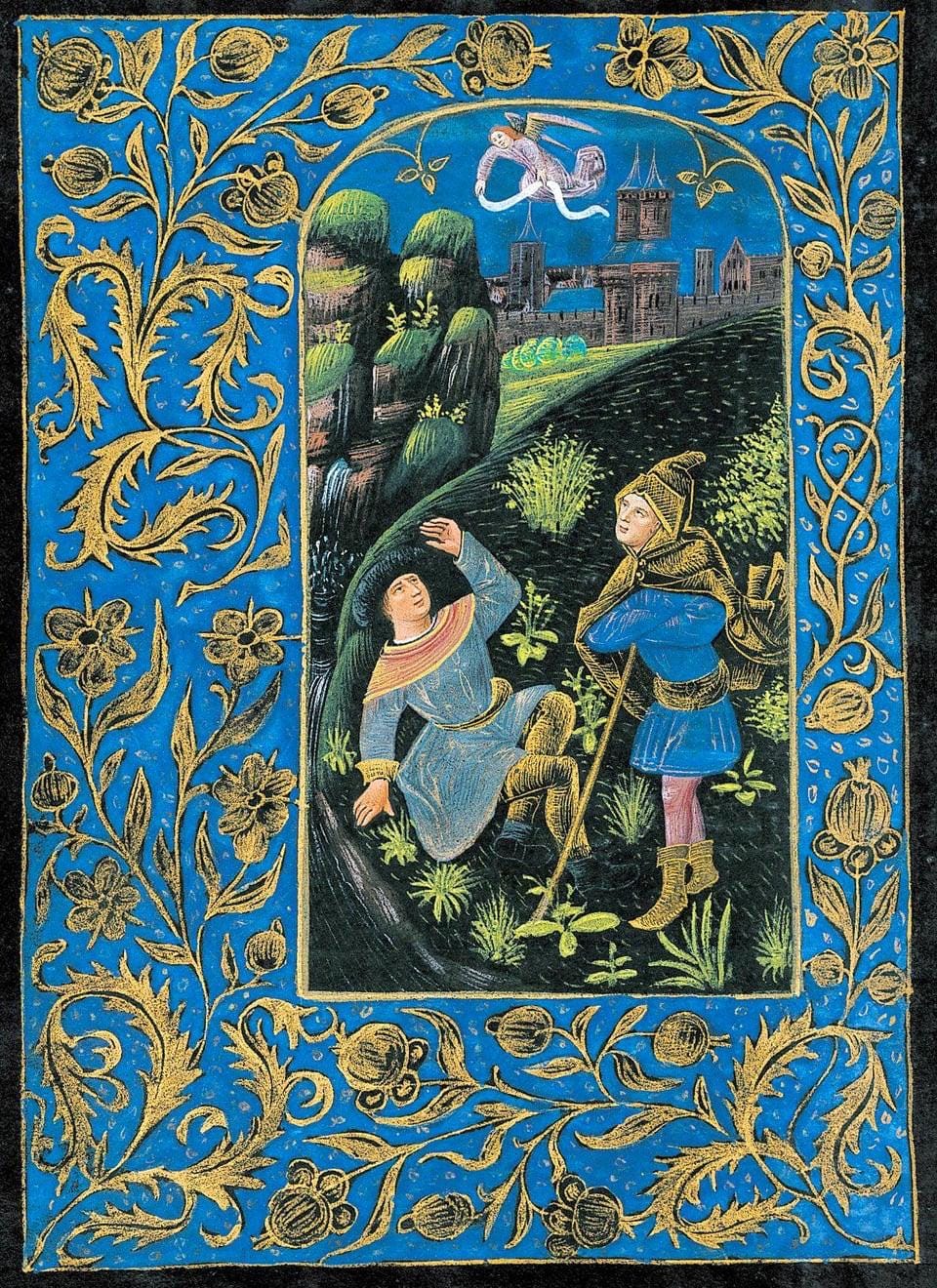

Picture taken from Book of Hours, MS M.493 fol. 54v, Belgium, Bruges, (c. 1480)

Whether you are a Christian or not, but even moreso if you are, maybe you have asked yourself: why should I read the ancients? What could possibly profit me from reading old ideas from antiquity or even Mesopotamia which are from a different or even alien culture to me?

And for Christians, especially in the fourth century onward, it was a very real question: the ancient authors were of pagan origin and touting the glory of false gods. How should one go about it? What would it profit our mind and soul to read them?

This is the question that Saint Basil of Ceasarea decided to answer in an text called "Address to Young Men on the Right Use of Greek Literature" in which he gives us compelling arguments to read them and profit from them, but also use discernment when doing so.

Introduction

This text was written in the fourth century by the Church Father Saint Basil of Cesarea. He was one of the Cappadocian Fathers, a group of influential Church Fathers who wrote on philosophy - epistemology, ontology and ethics - from a Christian point of view while also dealing with deep and profound theological questions. The other member of this group were his brother, Saint Gregory of Nyssa and his friend Saint Gregory of Nazianzus. Saint Basil was given the title Great Hierarch alongside Saint Gregory of Nazianzus and Saint John Chrysostom, and the three of them have their feast together on January 30th.

From the text itself, we can infer that Saint Basil had a few pupil or students and was helping them in their education. One aspect of this was to answer to them "what to do with ancient pagan literature". It's important to note that the context is key to understanding why he felt he needed to answer this question: in the fourth century, Christianity was newly recognised and no longer threatened by the imperial state. That being said, there were a whole apparatus, both politically and pedagogically, that was still immensely pagan. Whether following the path of the rhetors and paideia, the Greek education, which saint Basil himself did, or the liberal arts path in the Latin west, there were a plethora of pagan intellectual milestones to get through. Most ancients had read Plato for example, and to work out their grammar, either Homer in Greek or Virgil in Latin. For these reasons, Christians basically 'had' to read pagans if they were in the world or did their education in it. Then the question was: "how to do it right". This is what the text want to address. It does so with a main thesis and supporting arguments, but also from a meta-perspective: the text itself is loaded with quotes from pagan Greeks to prove that we can find both wisdom and virtue in them.

What is the book about as a whole?

The main thesis of Saint Basil with regards to this issue can be summarised as such:

- The GOAL of the christian life is eternal life in God

- This ETERNAL LIFE IN GOD is understood through the Scriptures (by the work of the Holy Spirit)

- THE SCRIPTURES cannot be approached unless one is prepared

- PREPARATION FOR HOLY SCRIPTURES goes notably through the use of pagan literature

- PAGAN LITERATURE is therefore useful when it extols the virtue and knowledge, and harmful when it promotes the passion and vices

What is being said in detail, and how?

Saint Basil presents three main arguments to support this view:

- Arg 1: The Bible gives us examples of men who did exactly that, studying pagan lore to better follow their Lord and God, notably Moses amongst the Egyptians and Daniel amongst the Chaldeans. Although not mentioned, we could add that some of the Church Fathers and many early Christians such as Saint Dyonisus, Saint Justin Martyr, Saint Augustine, etc. all fit into this category since they started as learned men of pagan origin and became not only good christian but saints and martyrs.

- Arg 2: Some of these texts are full of depiction of virtues, and some of their writers (or just important figure of these cultures) showcased virtue that is decidedly Christian. We should therefore look at them only for the good while discarding the bad since we know the good to exist in them. A good analogy for this is the analogy of bee that Saint Basil gives us:

For just as bees know how to extract honey from flowers, which to men are agreeable only for their fragrance and colour, even so here also those who look for something more than pleasure and enjoyment in such writers may derive profit for their souls. Now, then, altogether after the manner of bees must we use these writings, for the bees do not visit all the flowers without discrimination, nor indeed do they seek to carry away entire those upon which they light, but rather, having taken so much as is adapted to their needs, they let the rest go. So we, if wise, shall take from heathen books whatever befits us and is allied to the truth, and shall pass over the rest.

Another given analogy is taken from Greek mythology itself, "but when they portray base conduct, you must flee from them and stop up your ears, as Odysseus is said to have fled past the song of the sirens".

- Arg 3 (the 'wager' argument): If the texts are bad, then the contrast will help us appreciate the Scriptures more. If they are good, then they provide a better understanding of the Scriptures. In both cases, the Christian, if using right discernment, can profit from these texts.

His conclusion is then that we should read with a discriminating mind - that is, taking the good and leaving the bad - the texts of the pagan in search of virtue and other goods. This will help us form our mind to higher and more spiritual matters, as a soldier practices in training before going to war.

How this is done is clearly expressed when Saint Basil says that "we place our hopes upon the things which are beyond, **and** in preparation for the life eternal". This is two points: first, there are the things beyond (immaterial truths and states), and secondly, preparation for Life Eternal. Within the text, we can understand that virtues can be both: truths beyond and preparation for Life Eternal when actualised in oneself. This is why he puts so much emphasis on pagan literature's depiction of virtue. Hence, Holy Scriptures teaches us how to attain Life Eternal and what it is, and from this, we can evaluate pagan literature. There is therefore an hermeneutical circle: Holy Scriptures teaches us the "what" we should aim for and so how to judge the value of things in the world; then, the things of the world (including here pagan virtues and pagan literature) help us understand better the Holy Scriptures, or even straight up influence us into practising what is contained in them. As he says himself: "we exercise our spiritual perceptions upon profane writings, which are not altogether different, and in which we perceive the truth as it were in shadows and in mirrors". We can then conclude that pagan texts are reflections of the truth contained in the Holy Scriptures, not totally different from the idea of the logos spermatikos of Saint Justin Martyr. These pagan ideas then are "necessities of life" in so far as we are too immature to grasp the Holy Scriptures from the get go:

become first initiated in the pagan lore, then at length give special heed to the sacred and divine teachings, even as we first accustom ourselves to the sun's reflection in the water, and then become able to turn our eyes upon the very sun itself.

Is the content true, good, beautiful? In whole or in part?

This text is extremely important for Christians. First, it serves to dismantle the puritanical argument that we shouldn't read non-Christian texts. Secondly, it serves to orient us in our quest towards understanding Holy Scriptures, especially in our modern day and age where we lost a lot of the proper understanding of the text and its symbolism. Thirdly, it gives us a criteria by which to read non-Christian texts. On the topic of reading non-Christian texts, it's important to understand that not everything pre-christian is even necessarily pagan. On this topic, I suggest watching a clip by Seraphim Hamilton:

I believe this text to be truthful for these reasons. It is however important to mention that for some that eschew the world, such as monks, this text will arguably be received differently. But for us in the world, it is an aid to reach out for the good in a very concrete manner, especially when dealing with our decidedly non-Christian culture. (How can we recognize that? I like how Vesper Stamper at the recent Symbolic World Summit described it: we live in a world of raw power and fatalistic opportunism)

What of it?

I also think that one consequence of accepting Saint Basil view means that fiction and fantasy can get rehabilitated. What I mean is that some consider most imaginative literature as being negative, supposedly because it is not a Christian theoretical essay on deep theological truth - as if we would be able to understand all of those! First of all, there are many types of literature, such as theoretical, practical but also imaginative. They all have their own different aim and worth. Imaginative literature aims to share experience, which can be valuable. Just think of Dostoevsky and other Christian Orthodox writers. Secondly, imaginative literature, like the other two, can be very much Christian even if it is fantastical. A good example of this is the work of JRR Tolkien: he himself said in letter 153 that he wrote "for the encouragement of good morals in this real world.". By reading "On Fairy Stories" by the same author, you can get a much better grasp of this and the connection to the spiritual realm through the unique capacity of humans for what he calls subcreation. Thirdly, if we can make good use of pagan imaginative literature according to saint Basil, notably by looking at what virtue or knowledge it increases in us, how much moreso should we make good use of Christian imaginative literature? This supports the view of someone like Dr. Martin Shaw who keeps hammering the fact we are a mythos-deprived society, not a logos-deprived society.

Of course, Saint Basil also mentions that all of this reading of pagan literature is only valid if we actually look for truth and virtue in the Holy Scriptures. For truth, in order to adequately aim for the Eternal Life but also to be able to assess what we read in the pagan texts. As he himself says:

To be sure, we shall become more intimately acquainted with these precepts in the sacred writings, but it is incumbent upon us, for the present, to trace, as it were, the silhouette of virtue in the pagan authors.

For virtue, he himself says:

Now this is my counsel, that you should not unqualifiedly give over your minds to these men, as a ship is surrendered to the rudder, to follow whither they list, but that, while receiving whatever of value they have to offer, you yet recognise what it is wise to ignore.

Basically, even if we can profit from these things according to a positive reading, we must also understand that from the context of his era, where everything was mostly pagan literature, his position is still "restrictive" in a sense, especially with regards to virtue. For example, whole sway of mythology (especially the Greek one) with unbridled passions in the gods should not be read positively. In our case, the majority of the current literature accessible of the past is Christian and of the present post-Christian (that is, it still uses the same principles and presuppositions in terms of epistemology, ontology and sometimes ethics; this also include science). However, we should still read it with a discerning mind but it is undeniably more aligned with our worldview than it was during Saint Basil's time, meaning there is still good to be found in them.

In all his chapters, Saint Basil comes back again and again to the matter of paying attention to passions. We read those texts to develop virtue against passions. According to him, we should not give too much attention to passions of the body since, according to the expression of Plato, it is an aid to wisdom, not an end in itself. As Saint Basil says, which artisan would pay more attention to his tools than to his art? This leads Saint Basil to address this point:

'What then are we to do?' perchance some one may ask. What else than to care for the soul, never leaving an idle moment for other things? Accordingly, we ought not to serve the body any more than is absolutely necessary, but we ought to do our best for the soul, releasing it from the bondage of fellowship with the bodily appetites; at the same time we ought to make the body superior to passion. [...] Only give so much care to the body as is beneficial to the soul.

The measures of need should be the necessities of life, not the passion or the pleasure; and this should become our criteria for choosing what to read.

Have a good reading!